The origins of the development of branding can be traced back to pre-historic times. It may have first begun with the branding of farm animals in the Middle East in the Neolithic period.

The proof of it is believed to be found in the Stone Age and Bronze Age cave paintings which depict images of branded cattle and also in Egyptian funerary artwork which too depicts branded animals [ Briciu, V.A, and Briciu, A., “A Brief History of Brands and the Evolution of Place Branding”].

The historical perspective of brands evolves “from focusing on ownership to emphasizing quality” (Yang et al., 2012, p. 316) and the information which indicates the origin of the product (Moore and Reid, 2008, p. 6).

The modern discipline of brand management is considered to have been started by Neil H. McElroy at Procter & Gamble in 1931 while he was working on the advertising campaign for Camay soap. [“Neil McElroy’s Epiphany”. P&G Changing the Face of Consumer Marketing. Harvard Business School. May 2, 2000. Retrieved March 9, 2011].

Mid 1960s

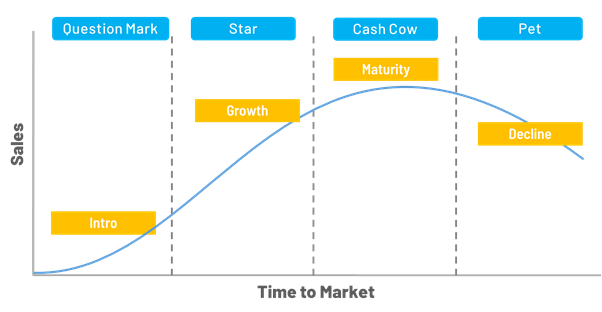

Theodore Levitt in 1965 penned an extensive discourse on Product Life Cycle (PLC). He went on “to suggest some ways of using the concept effectively and of turning the knowledge of its existence into a managerial instrument of competitive power” [“Exploit the Product Life Cycle”, Harvard Business Review (from the Magazine, November 1965)].

He analyzed the 4 Stages of PLC (Market Development, Market Growth, Market Maturity, and Market Decline) and noted his observation on the action points related to market dynamics, pricing, distribution with just one reference to “brand” – “Instead of seeking ways of getting consumers to try the product, the originator now faces the more compelling problem of getting them to prefer his brand.”

He concluded his observation by saying that a successful product strategy should look ahead over some years and “be viewed as a planned totality” for companies interested in continued “growth and profits.”

Later, in 1968, the growth-share matrix was created by BCG’s founder, Bruce Henderson. It was considered to be a tool to help companies allocate resources on the basis of the attractiveness of their market and their own level of competitiveness.

In Henderson’s words, to be successful “a company should have a port-folio of products with different growth rates and different market shares. The portfolio composition is a function of the balance between cash flows”. At the height of its success, the growth-share matrix was used by about half of all Fortune 500 companies. His much-celebrated and provocative essay paved the way for others in plotting theories in the similar fashion of the 2×2 matrix.

Both the Product Life Cycle and Growth-Share Matrix remain relevant today and are still central in business school teachings on strategy. Clearly, both the frameworks focus on Product-Market relations and subsequent resultant actions. One can deliberate the relationship between the frameworks.

The difference between the BCG Matrix and the Product Life Cycle as we know it –

1. The business is divided into four categories basis two aspects of market share and anticipated growth rate; however, the PLC is divided into four stages basis two aspects of sales and time.

2. The BCG Matrix can roughly judge an enterprise’s overall operating conditions, but the PLC only reflects the market performance of a single product.

3. The BCG matrix mainly studies the allocation and use of an enterprise’s resources, but the PLC mainly studies the use of the product marketing strategy.

4. The BCG matrix can reflect corporate a variety of different business conditions, but the PLC cannot reflect all businesses and products in the curve.

Henderson made a pertinent point – “No product market can grow indefinitely. The payoff from growth must come when the growth slows, or it never will. The payoff is cash that cannot be reinvested in that product.”

Brand and Source of Business

Rightfully the product is the core of any offering, whether tangible or intangible. One can argue that a product becomes a brand when it comes to communicating to consumers, by applying available methods to create a mind-space.

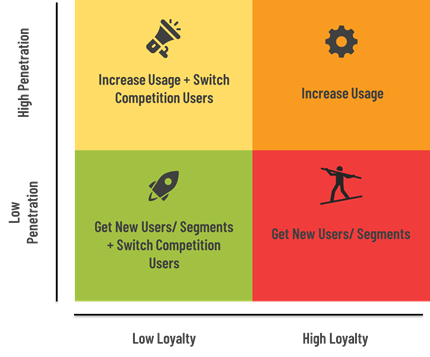

However, both the relevant frameworks with their strategic roles do not elaborate the significance and role of a brand. Much like a product, a brand goes through its life-cycle, and its role is to penetrate, grow the preference, and ultimately build loyalty towards it. This leads to a pertinent point on Brand Growth Objectives – what should be the “Source of Business” for a brand?

The answer lies in analyzing 2 variables of the category in which a brand exists – Penetration and Loyalty. There are basically 3 ways of growing a brand based on these two variables –

1. Get new users – tap new segments and/or switch competition users.

2. Get existing users to use more – increase usage.

3. Retain existing users – create brand loyalty (a default objective all the time).

This becomes the starting point on which one must be very clear before developing the brand strategy.

The ANBI (Anand Narasimha -Biplab Dasgupta) Brand Growth Matrix directionally identifies the growth objective based on which quadrant a brand is currently in. It forms the vision for the brand strategy. We have then looked at it if this can be translated into specific tasks which could be part of a brand plan – the execution guide, the brand actions.

It should tell us singularly the actionable initiative it requires but it doesn’t include any specific media mix which will vary based on which industry, the category it operates in, and its history and life stage.

Brand Actions

Each of the four quadrants represents a specific combination of action points on penetration and loyalty.

1. Low Penetration, Low Loyalty. Market development and brand extensions for new segments. Differentiation-driven campaigns and sales promotions for competition users.

2. High Penetration, Low Loyalty. Increase frequency of use, extend usage occasions, create new uses, cross-sell/up-sell. Differentiation-driven campaigns and sales promotions for competition users.

3. High Penetration, High Loyalty. Increase frequency of use, extend usage occasions, create new uses, cross-sell/up-sell.

4. Low Penetration, High Loyalty. Market development and brand extensions for new segments.

In addition, loyalty programs and CRM to retain existing users, need to be done in all 4 situations. A brand cannot afford to be a ‘leaky bucket’ where existing users are lapsing, while new users are being acquired.

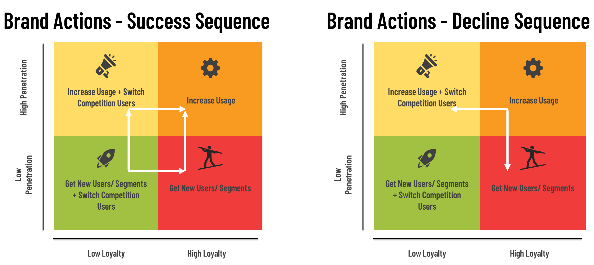

The ANBI Brand Growth Matrix reveals two factors that companies should consider when devising the brand strategy and actions – how much and where to invest – competitiveness and attractiveness of the brand and its potential. The allocation of resources will depend on that. Just like the life cycle of a product, there ought to be the sequences of success and decline paths.

The Success Sequence estimates the path a brand ideally should move in basis the quadrant it is currently in. In a situation where a High Penetration, High Loyalty (HPHL) brand slips, we estimate that it will slip to either High Penetration, Low Loyalty (HPLL) quadrant or to Low Penetration, High Loyalty (LPHL) quadrant.

In both the Decline Sequences, the problem must be identified quickly and brand should be refreshed to win back the consumers. To echo the words of Neil McElroy’s formula for P&G’s success, it is to “Find out what the consumers want and give it to them.”

Conclusion

Henderson’s observation of “No product market can grow indefinitely” gives rise to the thought of which brand to invest in or not. The concept of “Power Brands” may be handy to define the trajectory of a brand – its contribution to the overall kitty of a company and the extent of focus it still attracts, internally and externally.

To modify Henderson’s comments it is only a diversified company with a balanced portfolio of brands that can use its strength to truly capitalize on its growth opportunities.

This involves three key steps: accelerating the pace of innovation; balancing the investment between the brands basis brand objective; and carefully measuring and monitoring the brand’s penetration and loyalty metrics. The result will be a brand strategy that includes a plan for a timed sequence of conditional moves.

The Author has written this piece with Biplab Kumar Dasgupta: An ‘industry agnostic’ seasoned Marketing specialist with pan-India roles. Experienced in start-up and green-field operations – building from scratch and handling teams with strategic and large execution capabilities. Worked with Hutch, Lafarge, Giordano, Telenor, Reliance Communications, Rediffusion, and Bates. Last assignment was as the Founder & Director of a technology start-up. Currently, I am a Marketing Consultant and helped launch some startups. An occasional blogger on start-up, brand and business.

-AMAZONPOLLY-ONLYWORDS-START-

Also, check out our most loved stories below

Johnnie Walker – The legend that keeps walking!

Johnnie Walker is a 200 years old brand but it is still going strong with its marketing strategies and bold attitude to challenge the conventional norms.

Starbucks prices products on value not cost. Why?

In value-based pricing, products are price based on the perceived value instead of cost. Starbucks has mastered the art of value-based pricing. How?

Nike doesn’t sell shoes. It sells an idea!!

Nike has built one of the most powerful brands in the world through its benefit based marketing strategy. What is this strategy and how Nike has used it?

Domino’s is not a pizza delivery company. What is it then?

How one step towards digital transformation completely changed the brand perception of Domino’s from a pizza delivery company to a technology company?

BlackRock, the story of the world’s largest shadow bank

BlackRock has $7.9 trillion worth of Asset Under Management which is equal to 91 sovereign wealth funds managed. What made it unknown but a massive banker?

Why does Tesla’s Zero Dollar Budget Marketing Strategy work?

Touted as the most valuable car company in the world, Tesla firmly sticks to its zero dollar marketing. Then what is Tesla’s marketing strategy?

The Nokia Saga – Rise, Fall and Return

Nokia is a perfect case study of a business that once invincible but failed to maintain leadership as it did not innovate as fast as its competitors did!

Yahoo! The story of strategic mistakes

Yahoo’s story or case study is full of strategic mistakes. From wrong to missed acquisitions, wrong CEOs, the list is endless. No matter how great the product was!!

Apple – A Unique Take on Social Media Strategy

Apple’s social media strategy is extremely unusual. In this piece, we connect Apple’s unique and successful take on social media to its core values.

-AMAZONPOLLY-ONLYWORDS-END-